Behind the curves

Tensile structures add exciting new dimensions —and distinct engineering challenges— to the commercial shade products market.

It could be said, like the mythical Greek lion-goat-snake beast the chimera, that the tensile awning is a creature of blended ancestors. Not long ago, structures with tensile fabric characteristics started appearing in places often reserved for framed awnings or canopies, begging the question: What is the difference between an awning and a tensile awning?

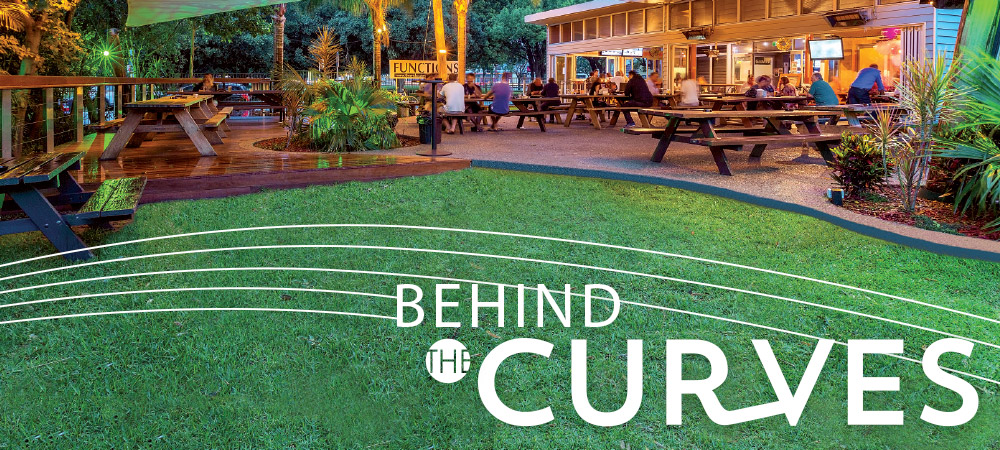

The Wickham Park Hotel of Newcastle, Australia, commissioned Shade to Order to design, fabricate and install a freeform tensile shade structure over its outdoor eating plaza. Photo: Shade to Order Pty. Ltd.

That’s a conundrum the Fabric Structures Association (FSA) and the Professional Awning Manufacturers Association (PAMA), both divisions of the Advanced Textiles Association (ATA), have been grappling with for more than a decade. New designs of more shapely shade and awning constructions have appeared, combining aspects of standard frame-based awnings with the more complex engineering of tensile structures. They are neither straightforward frame awnings nor, strictly speaking, by themselves freestanding tension structures.

“There are two bold-face answers to the question as to the differences,” says Craig G. Huntington, SE, F.ASCE, president of Huntington Design Associates Inc., Oakland, Calif., consulting structural engineers. “First: curvature. Traditional awnings are uncurved, which sharply limits both their potential visual expressiveness and their spanning capability. Traditional awnings can be made large by the addition of a lot of intermediate framing, so long as the fabric spans themselves are limited to a few feet, while the introduction of double curvature in tensile awnings allows much longer spans for the fabric itself, and also limits the deflection of the awning under wind load.

“Second: pre-stress. Traditional awnings,” says Huntington, “are pulled to their perimeter, with minimal fabric pre-tensioning provided by lacing cords or by pulling a keder track out to the supporting structure. Tensile awnings incorporate operable cable fittings or other devices to create significant pre-stress. The pre-stress prevents wrinkling of the membrane and holds the membrane stable under varying wind loads to prevent flutter.”

Throwing curves

In the simplest terms, a standard awning is a structural frame for rigidity that is clad with fabric. Yet from an engineering standpoint, even that definition needs clarification to better understand how an awning interacts with the building to which it’s attached. “The frame transmits the wind and snow forces to the building nearly the same whether the cladding is steel deck or fabric,” says Wayne Rendely, PE, Huntington Station, N.Y., consultant structural engineer. “The frame also resists the internal fabric tension forces.”

Rendely, like Huntington, has made a study of fabric-clad structures and knows that stretching thin, membrane-like materials over armatures requires special knowledge of dynamic stresses and material connections. “Tensile awnings might use spars and cable tiebacks, and the internal forces of the fabric are supported either by a frame or by direct anchorage to the building,” says Rendely. “Traditional awnings typically have lower anchor forces. The tensile awning typically has a unique architectural quality,” but much higher lateral forces.

The Avery Aquatic Center at Stanford University features a pair of tensile canopies that face each other, arching over the bleacher seating for the diving pool. Photo: Huntington Design Associates Inc.

“Tensile awnings, being mainly fabric and cables,” says Mark Welander, MFC, owner of Fabricon LLC, Missoula, Mont., “have little or no rigidity and rely on tension or pre-stress in the fabric to provide the form and support. Traditional awnings are generally less expensive to design and build, while tensile awnings can provide an attractive and unusual look.” They also cost significantly more.

“The main difference that sets these [types of structures] apart from standard window awnings is the relatively larger span of fabric,” says Erik Jarvie, sales engineer with Tension Structures (a division of Eide Industries Inc., Cerritos, Calif.). In order to design a responsible tensile awning, the engineering standards and practices need to be more thorough [than with standard awnings].” This is not to say that standard awnings are simple to design or less visually interesting. Unusual awnings with bright colored fabrics and graphics can be constructed by adding framed solid shapes together to achieve more complex designs. However, integrated forms that are structurally contiguous should be designed as tensile structures to ensure stability.

Distinct advantages

What are the advantages for each type of shade structure? Like many things, it depends. “Many traditional awnings are installed in places where a tensile awning would not be suitable, such as historic buildings and houses,” says Craig Flanagan, owner of Shade to Order Pty. Ltd., Gateshead, NSW, Australia. “The domestic residential client generally wants his awning to be attached above windows or around the roofline of a veranda. There are some exceptions, but a tensile awning is not suited to the residential client, as the pre-stress loads the fabric transfers to the attachments are too high. A stand-alone tensile structure is more suited for the commercial client. The freedom to design with tensile architecture is high, and shapes can be achieved that cannot be easily achieved with conventional building methods.” A well-designed tensile structure can cover large distances between support columns or rafters, and the price per square meter can be more economical for larger structures, says Flanagan.

The curved triangular truss of the Wyong Rugby League Club porte cochère is held in place by two very large stainless steel pins at each end. In a neat trick of efficiency, the universal beam also acts as a rain gutter. Photo: Shade To Order Pty. Ltd.

What special skills or capabilities are needed to successfully construct a tensile awning? Because double curvature fabric relies on tension to maintain its structure and shape, “an awareness of torsional and lateral loads is a must,” says Jarvie, “as is the ability to model and pattern the curvilinear shapes compensating for pre-stress.

“Engineering for a standard window awning requires some basic calculations to verify rafter sizing and spacing. Tensile structures require 3-D modeling and finite element analysis (FEA) of the fabric, frame and cables. The FEA output will verify loads, stresses, member sizing, fabric displacement and possible ponding issues,” says Jarvie. “Without accurately checking all these outputs, there is a high chance for awning failure under extreme load conditions (wind, rain, snow, etc.).”

Echoing that concern, Rendely stresses that fabricators constructing tensile awnings need to work from the drawings provided by a tensile fabric engineer, architect or designer.

“The designer needs a good understanding of the proposed structure,” says Flanagan. “What shape will it be? Freeform, conical, barrel vault or a combination of two or more structures? Catenary cable edges, structural beam edges, columns or attachments? And the designer must have some idea of the fabric that is to be used. He has to try to balance all this with the client’s wishes. The more information he can go to the engineer with, the less time the engineer will spend on the structure, resulting in reduced fees.”

No matter what shape…

As a cost-saving alternative to a glass-and-steel entry canopy, this tensioned fabric canopy provides shade and internal rainwater drainage through inverted fabric cones. Photo: Huntington Design Associates Inc.

Time is also a factor when it comes to tensile awnings. “From our perspective, the design and execution of a shade structure project is a philosophical one,” says Joe Belli, president of Eide Industries. “We think more on a long-term basis (meaning a couple of years) with regard to tensile projects. Whereas, with awning projects it is usually short term … in and out, from start to sign-off.” The process of developing a design and creating a project for a client is also like night and day between the two types of structures, says Belli. “With traditional awnings, the time frame is on the order of weeks or a few months, versus a tension structure that may take a couple of years and involve any number of aspects, including liability insurance, errors and omissions insurance and other important protections for the client and the manufacturer.” According to Belli, a considerable amount of attention is required to see a project through to completion due to changing site conditions, engineering analysis, design detailing, design refinement, customer needs changes, etc.; when designing tensile projects, there are scores of unknowns from the beginning.

“Tensile awnings should have a certain degree of 3-D shape,” says Flanagan. “The 3-D fabric surface and fabric pre-tension maintain the original designed shape of the structure. This is what you have sold the client, and this is what they expect over the structure’s life span. Tensile structures generally move around very little in high winds. Little movement means the columns, rafters and attachments will not be stressed at awkward angles. No one wants to see their tensile structure moving or pumping in high winds, especially the engineer.”

“With proper input of variables (pretension, material properties, load conditions, etc.),” says Jarvie, “the FEA software will typically confirm member sizes that are much higher than the standard window awnings. This is where costs come into play.”

Materials and connections

Tensile awnings have extra requirements, including strength of materials used, fastenings/rigging and anchoring.

An unusual illuminated structure for The University of Alaska Fairbanks Native Studies Center was designed to protect against the dark, snowy winter and reflect an Athabascan fish trap. Photo: Fabricon LLC

“Because [doubly curved] fabric relies on internal tensile forces to remain stable, its response to loads is more complex than their traditional counterparts,” says Welander, “and understanding these simple principles is essential when designing. Fabrics used under tension need to be relatively stable.” Many fabrics and meshes—including acrylics, HDPE, nylons, even polyesters—have a tendency to stretch over time, and re-tensioning could become a necessity until something gives—and that something may not be the fabric. This must be factored into the design, or assume follow-up maintenance.

“The connection details may need to accommodate movement as well as greater forces,” says Rendely, “and the anchors need to be addressed by a professional engineer.”

“Tensile structures require a fabric that has excellent structural properties,” says Flanagan. “The fabric is designed for this purpose. This type of structure will have a high amount of pre-stress and requires larger footings [than awnings or canopies], increased structural steel columns or beams and attachments strong enough to handle the transfer loads to a fixed location. The supporting cables and elements in tension are generally slender, but strong, for the size of the structure, and this can result in the fabric skin appearing to be supported by very little infrastructure.”

“The engineering and fabrication demands on tensile awnings are just small-scale versions of those for large tension structures,” says Huntington, “including the following: 1) Three-dimensional FEA of the structure is required in order to reasonably reflect the complex behavior of the curving membranes and cables, and the expected deformations under load; 2) patterning of the membranes is required and cables must be set to analytically determined lengths; 3) in developing cable attachments, the geometry of the steel must be set to accommodate the membrane form and cable lengths determined in the patterning process.”

In the beginning

All the experts consulted for this article agree that it’s best if the fabricator-engineer team is brought in at the beginning of a project before construction commences. “A tensile awning is best designed during the design of new construction,” says Rendely. “Structural anchors should be designed to accommodate the tensile awning forces. This is especially true if an awning of large scale is to be considered. The challenge is when working with existing structures and the forces involved with tensile fabric. Brick [facing] is not structural.”

Tensile awnings grace the PGA West Stadium Clubhouse in La Quinta, Calif. Stainless steel catenary cables and fittings use pinned and bolted connections to ensure an economical and quick field installation. Photo: Eide Industries Inc.

“The [existing] structure needs to be able to handle the lateral loads,” says Welander. “Often a tensile awning would be aesthetically preferable, but the structure is not capable of supporting the loads exerted unless additional reinforcing can be done to the building or a frame is developed that can handle the situation. There also needs to be adequate clearance for ties or hold-downs if needed. A standard awning footprint usually ends at the bottom of the frame, while a tensile awning often needs to use hold-downs below the fabric.”

Advising a client depends on the conditions of the building in question or local wind/rainfall or snow load conditions. “Generally if the client requires a larger structure that needs to keep the designed shape over its life span, or the client is considering a fabric structure instead of a structure built from more conventional materials like timber or steel roofing, we would advise going tensile,” says Flanagan. “If the client’s needs are to have a covered area exposed to high winds, high rainfall or installed in a high fire rating area, a tensile structure is more suited.”

“The customer really needs to have a strong desire for a tensile awning in order to overcome the price tag that is often double that of a standard awning,” says Jarvie. “The ROI for a tensile awning is usually justified for resorts and restaurants that are trying to set themselves apart from the fray. Residential and industrial projects are much more difficult to rationalize.”

So are you behind the curves? As the allusion at the beginning of this article tells us, the answer depends on your perspective.

Bruce N. Wright, AIA, a licensed architect, is a media consultant to architects, engineers and designers, and writes frequently about fabric-based design.